The gap between telehealth haves and have-nots threatens to undermine the momentum toward Pharma virtual care.

Owing to a combination of stay-at-home orders and the federal government’s temporary expansion of coverage for telehealth services, COVID-19 catalyzed the adoption of telehealth. But while the surge has benefited both patients (hello, getting diagnosed on the couch) and doctors (who report having more time to speak with patients and caregivers, according to ZS research), a divide has emerged among telehealth haves and have-nots. Indeed, many of the preexisting barriers to care are being replicated in the digital realm.

So, as pharma marketers continue adapting to the world of virtual care, it’s critical to understand who telehealth isn’t reaching — and how their efforts can bolster equity in telehealth access.

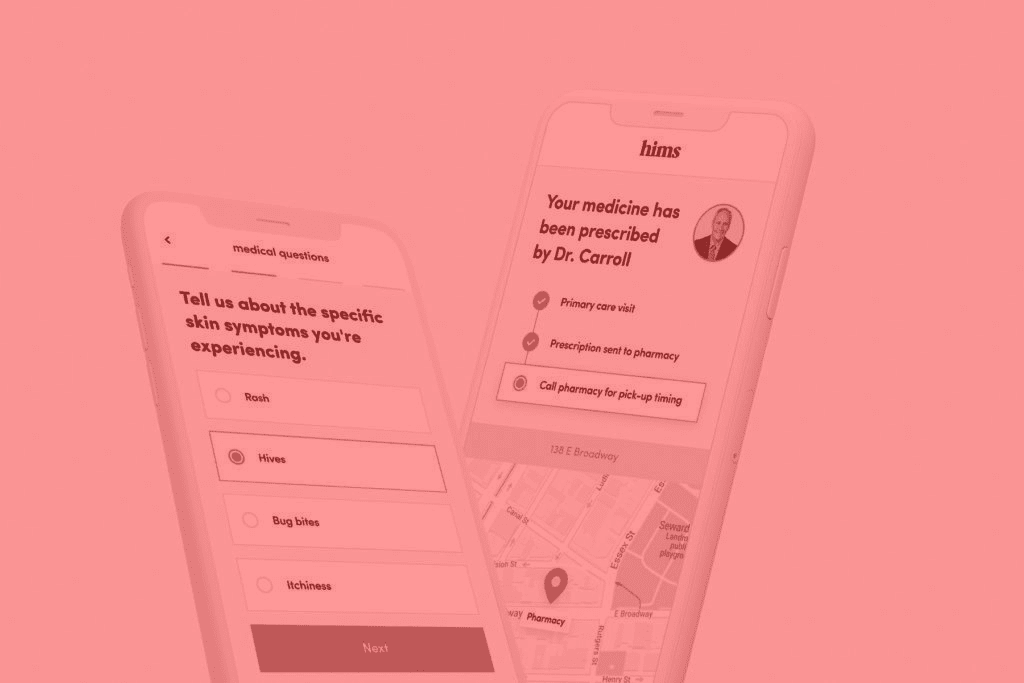

The increasing divide serves to blunt industry momentum toward widespread telehealth adoption, which has obvious implications for medical marketers. At the start of the pandemic, point-of-care marketing quickly shifted from physical pamphlets and posters to two-minute informational messaging that plays in the virtual waiting room before patients connect with their doctors. Drug websites now encourage visitors to “click here to talk to your doctor,” connecting patients to vertically integrated telehealth practices.

Indeed, telehealth has become almost a marketing call to action. By way of example, Biohaven Pharmaceuticals’ Nurtec, a migraine medication that launched in 2020 with an assist from a telehealth firm that specializes in migraine care. The success of these types of activations depends on answering the question, “Did the telehealth option that brands were offering really solve a problem for the patient?"

After stratospheric levels of adoption in 2020 — IQVIA reported a 3,000% increase in users — telehealth claims have plateaued, though at a higher level than many in the industry expected. According to telehealth claims analysis by ZS, about 20% of patient visits will shift to telehealth long-term.

But none of this accounts for the telehealth users who have been left behind. In February, the NHIT helped launch the Telehealth Equity Coalition (TEC), a group of academics, telehealth providers and nonprofits working to identify barriers and advocate for public policy that increases access to telehealth among underserved groups, among them seniors, rural residents and low-income communities of colour.

The coalition’s website cites recent NHIT data on telehealth access showing that poorer and more rural states had fewer telehealth claims over the last year. Similarly, a study of COVID-related visits at New York City’s Mount Sinai Health System found that white and Asian patients were the most likely to use telehealth, while Black and Hispanic patients, people over 65 and non-English speaking patients were more likely to seek emergency room care.

First, there is the physical barrier of broadband access: The Federal Communications Commission reports that nearly 30 million Americans do not have access to high-speed internet, including 35% of people who live in rural areas.

At least 31.8 million American adults aren’t digitally literate, while many communities of colour have a history of distrust in the healthcare establishment. A recent poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation and The Undefeated found that six of 10 Black adults said they trust doctors to do what is right most of the time, compared to eight of 10 white people.

To better understand the interdisciplinary nature of these challenges, the NHIT is providing the Telehealth Equity Coalition and its members with access to the NHIT Data Fusion Center, which incorporates data sets from governmental organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Federal Communications Commission. By layering these data sets on top of each other, TEC can create data visualizations that show where’s the broadband, where’s the transportation, food insecurity, etc.

So how can pharma support equitable access to telehealth? One example: patient support programs most pharma brands already have in place, which offer everything from co-pay cards to health coaches and call centers for answering patient questions.

There’s a tremendous amount of support pharma can provide to patients to cover some of these disparities that we see with telehealth and care overall. However, too often patients and physicians aren’t aware of them.

Meeting patients’ technological capabilities, through increasing the availability of audio-only calls for those without broadband and focusing on mobile-first resources, is also an important piece of the equity puzzle. Advocates are currently pushing the US federal government to reimburse audio-only telehealth at the same rates as video calls.

According to a 2019 Pew Research Center study, 26% of adults earning under $30,000 a year are “smartphone-dependent internet users.” Pharma companies could, then, think about text-based messaging and reminder programs, short videos or snackable content that will enable them to reach the patient where telehealth is happening.

Besides that, an emphasis is needed on the importance of listening to community needs and including the communities as partners in the production of health.

Above all, we need to ask communities how they want to access healthcare services and operate within that framework, rather than imposing a telehealth solution onto them.

Sources:

- May 01, 2021 Issue of MM+M - Medical Marketing and Media

- Telehealth Claims - February 2021 IQVIA Report

- Paradigms for Telehealth access - Telehealth Equity Coalition

Tags: pharma virtual care, telehealth pharma, virtual care pharma